In 2019, a team of scholars at Cambridge University Library made a remarkable discovery, uncovering a 750-year-old text about the legends of King Arthur that had been hidden in plain sight. The text was found embedded in the binding of a 16th-century property record, which made it extremely challenging to study without causing damage to the record. However, thanks to advanced imaging techniques, the scholars were able to create a virtual copy of the binding, allowing them to digitally unfold the rare text without compromising the original document.

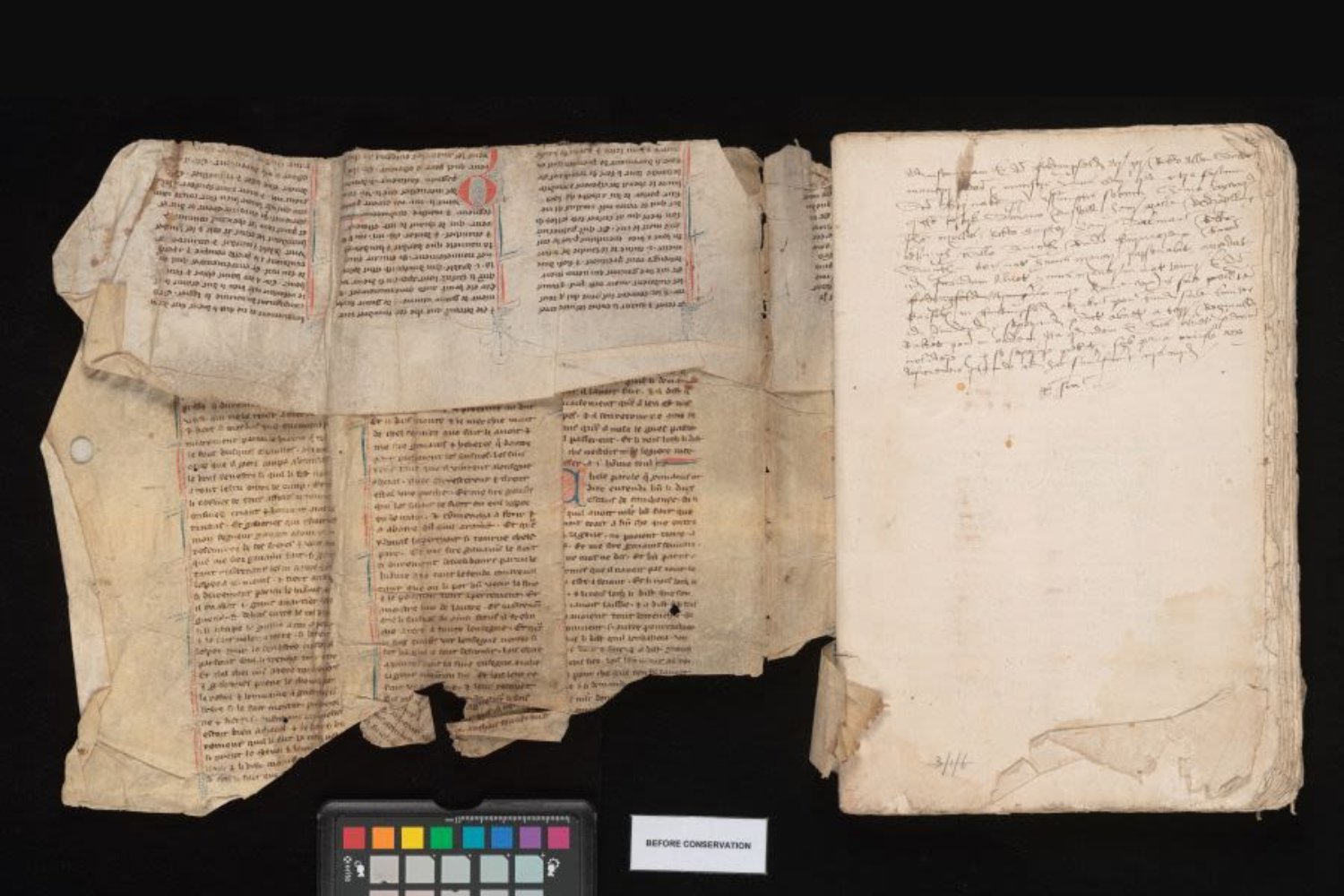

A multidisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Cambridge employed cutting-edge imaging techniques to photograph every aspect of the folded fragment, making the text more readable and creating a detailed 3D model of the artifact. This approach enabled them to understand the structure of the binding without having to disassemble it. By piecing together hundreds of images, the team created a digital version of the cover, which researchers can now study as if they were handling the actual artifact. According to Irène Fabry-Tehranchi, a French Specialist in Collections and Academic Liaison at Cambridge University Library who was involved in the project, this approach preserves the artifact as an example of 16th-century archival binding practice, which is “a piece of history in its own right,” as she explained in a university statement.

The team used a range of tools, including mirrors, magnets, and prisms, in addition to advanced imaging techniques, to capture every facet of the folded fragment. This allowed them to make the text more readable and create a highly detailed 3D model of the artifact, providing valuable insights into the structure of the binding without having to take it apart.

“If we had attempted to study this fragment 30 years ago, it might have been cut, unfolded, and flattened, causing irreparable damage,” said Fabry-Tehranchi. “But today, preserving it in situ gives us a crucial insight into 16th-century archival practices, as well as access to the medieval story itself.” Initially, the text was thought to be a 14th-century story about Sir Gawain, but further examination revealed it to be part of the Old French Vulgate Merlin sequel, a different and extremely significant Arthurian text.

The medieval legends of King Arthur, Queen Guinevere, Sir Lancelot, Merlin, and the quest for the Holy Grail have been retold and reinterpreted in countless versions over the centuries, spanning possibly over a thousand years. The Vulgate Cycle, also known as the Lancelot-Grail Cycle, is one such version in Old French.

Written in the first half of the 13th century, the Vulgate Cycle recounts the Arthurian legends in a monumental five-part epic prose. The fragment found at Cambridge University Library is from the Suite Vulgate du Merlin, a part of the Vulgate Cycle that recounts events that take place after King Arthur’s coronation. One passage from the fragment tells of the Christian victory over the Saxons at the Battle of Cambénic involving the knight Gauvin (also Gawain) with his Excalibur sword. Another recounts when a disguised Merlin appears at King Arthur’s court during the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. Here’s the English translation:

While they were rejoicing in the feast, and Kay the seneschal brought the first dish to King Arthur and Queen Guinevere, there arrived the most handsome man ever seen in Christian lands. He was wearing a silk tunic girded by a silk harness woven with gold and precious stones which glittered with such brightness that it illuminated the whole room.

There are fewer than 40 surviving copies of the Suite Vulgate du Merlin text known to scholars, and since medieval scribes copied them by hand, each is a unique version. The one found at Cambridge University Library, for example, has decorative red and blue initials. Based on this as well as other features, the researchers suggest the text was written between 1275 and 1315.

However, “this project was not just about unlocking one text—it was about developing a methodology that can be used for other manuscripts,” Fabry-Tehranchi concluded. “Libraries and archives around the world face similar challenges with fragile fragments embedded in bindings, and our approach provides a model for non-invasive access and study.”

One person’s trash (or book binding) really might be another person’s treasure—even 750 years later.

Source Link